Brash bigwigs used to get the glory, but then they started cratering companies.

Now the next great leaders look a whole lot more selfless.

By Robert Hogan, Ph.D., Ryne Sherman, Ph.D., and Scott Gregory, Ph.D.

The research is now crystal clear: Three psychological concepts—charisma, narcissism, and humility—impact leadership. Each is strongly correlated to leadership effectiveness and organization success.

So which concept should you choose? Before you pick, let’s dig into each.

The Theory of Charisma

Charisma is defined as “a compelling attractiveness that can inspire devotion in others.” It’s associated with stage presence and animal magnetism—the ability to attract attention to oneself.

The psychology of charisma can be traced back to Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) and his ideas about how hypnotism works. Mesmer argued that certain peculiarly gifted (charismatic) individuals, including himself, could put others under a hypnotic spell by the sheer power of their personalities.

Thus, ordinary people are often mysteriously drawn to charismatic people who, through a kind of hypnotic effect, persuade ordinary people to follow their orders—even if they don’t make any sense. The parallels with Adolf Hitler’s on-stage magic are obvious.

There are real individual differences in charisma; some people have it but most don’t. Some people are obviously more interesting than others. The entertainment industry, for example, is based on this fact. Movies are nothing more than vehicles for displaying charismatic famous people whom other people pay to watch perform.

We can rate the charisma of people with considerable reliability. It’s not clear, at least to us, whether people who are perceived as charismatic know this. But it’s clear that many people who think they’re charismatic aren’t hypnotic and mesmerizing.

Other writers trace the origins of charisma to Saint Paul’s letters to the emerging Christian communities. St. Paul observed that the Christian communities could recognize the true messengers of God by their (divinely inspired) charisma.

The great German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) linked St. Paul’s idea of charisma to institutional power. Weber observed that some people have power by virtue of the law (such as the members of the U.S. Supreme Court), some have power by virtue of their position in the institutional hierarchy (like CEOs), and some by virtue of their personal charisma.

Weber was the first person to link charisma to leadership. He proposed that revolutions are always led by charismatic figures, whose stage presence and animal magnetism attract followers. But for revolutions to truly succeed, bureaucrats must take over and run things more efficiently.

This is because, according to Weber, charismatic leadership is always disruptive. For revolutionary change to actually be successful, charismatic leadership must give way to “the iron law of bureaucracy.” Weber’s ideas about charisma and leadership have been widely influential.

The Theory of Narcissism

Most people know that the term narcissism comes from Greek antiquity, based on the fable of Narcissus and his fatal self-infatuation. Narcissism entered the mainstream of psychology in the late 19th century, when several psychiatrists—most famously Sigmund Freud—wrote essays analyzing narcissism as a kind of personality disorder. Narcissism is a behavioral syndrome that includes self-love, dangerous overconfidence, arrogant self-absorption, and lack of empathy or humility.

Even though charisma is something that observers attribute to actors, we know little about its actual origins. Narcissism is also something that observers attribute to actors, but unlike charisma, we know where it comes from. Narcissism is caused by a person’s unrealistically positive self-attributions. Individual differences in narcissism can be easily assessed with standardized personality questionnaires. A typical item would be, “Other people can sense my power,” to which narcissists answer “true.”

Narcissism can be valuable. It’s associated with the kind of courage that’s needed to take on large and risky projects and succeed where no one has gone before. Narcissism enabled Alexander the Great to conquer the entire known world east of Greece. It propelled Christopher Columbus to sail an uncharted ocean to America. It helped Hernando Cortes conquer Mexico against stupefying odds.

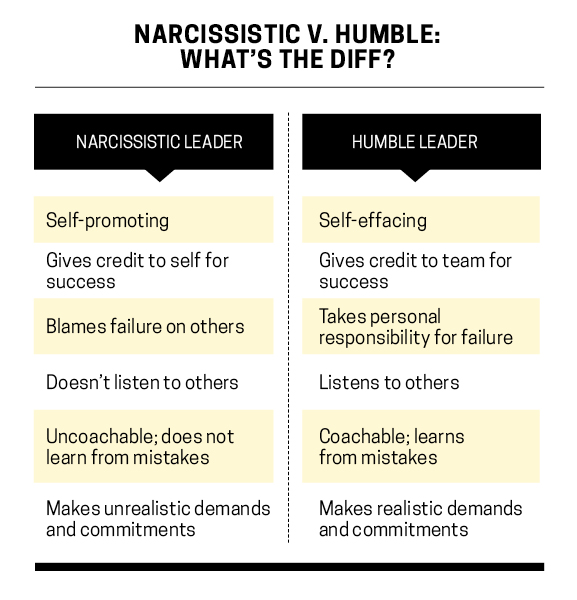

But narcissists also tend to bite off much more than they can chew. They may make impulsive and excessively risky decisions, ignore failure when it inevitably occurs, be unable to learn from experience, take too much credit for success and too little responsibility for failure, and treat subordinates like they’re disposable commodities.

The Theory of Humility

Narcissism is sometimes defined as the absence of humility. Humility, on the other hand, can be defined as “freedom from pride or arrogance: the quality or state of low self-preoccupation.”

The world’s great religions maintain that humility is the proper human stance in view of the vast and unknowable nature of the universe. Humility isn’t meekness or self-deprecation. It’s being willing to submit oneself to something “higher,” place others first, appreciate their worth, and recognize the limits of one’s talents or authority.

As Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry observes at the end of the 1973 movie Magnum Force while bringing down an arrogant and corrupt police official, “Man’s got to know his limitations.”

Humility and narcissism are psychological opposites, but they’re similar in that they can be easily seen and rated by other people.

Humility is also like narcissism in that it’s a kind of self-attribution (how people see themselves) and it can be easily assessed using standard psychometric methods.

A typical humility item is, “I am superior in many ways,” to which the humble answer is “false.” Typical behaviors associated with humility include being willing to admit mistakes, listen to feedback, treat others with respect regardless of their rank, and make fun of oneself.

It’s important to note how self-confidence relates to narcissism and humility. Self-confidence concerns the degree to which people feel up to the problems that confront them—their sense that they can complete the tasks they’ve been assigned or have undertaken. People with low self-confidence are defeated before they get started, while people with high self-confidence take on tasks and persist until they’re completed. Should they fail at a task, they dust themselves off and get ready for the next challenge.

Generally speaking, narcissists are too self-confident, and this has two consequences. On the one hand, they’re willing to take on tasks that few other people would attempt. On the other, they’re unwilling to admit personal failures. If projects don’t turn out well, the cause will be circumstances beyond their control: incompetent subordinates, betrayal, unforeseen changes in circumstances. But if projects turn out well, it’s because the narcissist was in charge.

In contrast with narcissists, who are always self-confident, humble people may or may not be self-confident. Humble people who lack self-confidence seem weak and indecisive. Humble people with self-confidence, meanwhile, usually project themselves well, like Tom Brady, the future Hall of Fame quarterback of the New England Patriots.

The Theory of Leadership

Leadership theories are like belly buttons: Everyone has one. But ideas have consequences, and these theories are more consequential than belly buttons.

In our view, the literature on leadership is plagued by two major confusions. First, most leadership research tends to focus on the individuals who are or who aspire to be leaders. The researchers gather data on these individuals and try to draw conclusions. But this approach hasn’t produced much consensus regarding the characteristics of effective leaders.

In contrast, we think leadership is a resource for groups—not a source of status for incumbents. People evolved as group-living animals, and evolutionary pressure acted on groups as well as on individuals within groups. Warfare was a major factor driving human evolution. Inside groups, the competition is for status (because of sexual selection), but between groups, the competition is for survival (because of warfare).

What’s good for the group is always good for its members. What’s good for individual members of groups may or may not be good for the group, because free riders exploit group membership for selfish reasons.

Human nature is ambivalent; people can both compete and cooperate with other group members. When a group is attacked by rival groups, it needs leadership to persuade members to stop competing and start cooperating. This is the sense in which leadership is a resource for the group.

It’s why we think that leadership should be defined in terms of the ability to build and maintain a high-performing team. Similarly, leadership should also be evaluated in terms of the performance of the team vis-a-vis its competition. Leadership isn’t about who’s in charge of a group—it’s about the group succeeding in its competition with rival groups. When you define leadership this way, real patterns and the characteristics of effective leaders begin to stand out.

The second confusion that characterizes most leadership theories concerns the distinction between leader emergence and leader effectiveness, one first highlighted in Fred Luthans’ classic 1988 book, Real Managers.

Luthans studied 457 managers from several organizations over four years, gathering assessment data on each boss and performance data at the end. He found that designated high-performing managers could be sorted into two groups, with a 10 percent overlap between them.

The first group contained people who received rapid promotions and pay raises, and the second contained people whose teams performed well. Because Luthans had extensive behavioral data on these managers, he could determine how they spent their time at work. The managers who received rapid promotions and pay raises spent their time networking, while those whose teams performed well spent their time working with their teams.

We think it’s essential to distinguish emergent leaders (those who are promoted rapidly) from effective leaders (those who build high-performing teams). Some people correctly argue that managers must first emerge before they can be effective. Nonetheless, a major reason why leadership research tends not to converge concerns the failure to distinguish between emergent and effective leaders.

The Theory of Charismatic Leadership

In the history of American business, publicly traded companies were clubby affairs, and CEOs tended to be benevolent caretakers with modest salaries compared to the rest of their organizations.

In the 1970s, activist investors like T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn began to push corporate boards for better results. This pressure, combined with Michael Jensen and William Meckling’s solution to the “agency problem” (that is, tying CEO compensation to firm performance via stock options) had a major consequence for CEO selection. Specifically, companies began searching for CEOs who seemed likely to deliver strong financial results.

These searches tend to turn up candidates who are highly emergent and promise to take the company to a new level. “Charisma” drives emergence and thus began the myth of charismatic leadership. People who seem charismatic also seem leader-like, but the data indicate pretty clearly that charisma is a poor predictor of leader effectiveness. What might account for this?

It turns out that because charisma is correlated with narcissism, narcissistic candidates always promise to bring better financial results. But research in Administrative Science Quarterly shows that narcissistic CEOs ruin companies by making extravagant bets and bad decisions.

Conversely, Jim Collins’ famous 2001 book Good to Great—which lays bare the characteristics of CEOs from high-performing companies—reports that there were no charismatic CEOs in his sample of elite-performing CEOs.

Humility and Leadership

Good to Great is about leadership effectiveness. Collins shows clearly that highly effective CEOs are humble, but they’re also persistent and fiercely competitive regarding the performance of their organizations. They don’t take themselves seriously, but they take the success of the business very seriously.

A 2017 study by the MIT Leadership Institute reinforces Collins’ finding. It shows that MIT alumni have started 30,200 businesses that collectively have 4.6 million employees and $1.9 trillion in annual revenue, which puts them (as a group) behind Russia, but ahead of India in terms of revenue generation.

The study authors describe MIT leaders as open-minded, collaborative, apolitical, and unapologetically data-driven. In addition, they avoid the trappings of traditional leadership, steering clear of corner offices and private planes.

Some exemplars of this humble leadership style include Sergio Marchionne (Fiat Chrysler), Alan Mulally (Ford), Hubert Joly (Best Buy), and Larry Culp (GE), all unusually successful CEOs.

Since the publication of Good to Great, research on humility and leadership has blossomed, led by Bradley Owens and his colleagues.

We now know that highly effective CEOs are humble, but what are humble people like? For starters, they acknowledge their mistakes, spotlight the contributions of other people, listen to and learn from others, make fun of themselves, and espouse egalitarian values.

And what exactly do humble leaders do? They focus on the team’s performance, not their own; they encourage learning and personal development for all employees; and they build a culture that encourages openness, trust, and recognition.

In 2015, Amy Yi Ou and her colleagues showed in the Journal of Management that humble CEOs reduce pay disparities among their top team members, reduce power struggles, foster team integration, and encourage equal participation in strategy formation—all factors that are proven to predict successful corporate performance.

So what, as a leader, can you do to demonstrate humility? Here are six places to start:

- Actively recognize the achievements of others.

- Work to understand your own limitations.

- Admit your mistakes—don’t explain them away.

- Ask for and listen to feedback.

- Work to earn the respect of your colleagues.

- Monitor yourself and control any self-promotional behavior.

In short, humble leaders are serious about their business, but don’t take themselves seriously. They can laugh at themselves and admit their flaws so that they can improve their performance.

Humble leaders are concerned about their staff, their well-being, their development, and their ability to contribute to the team’s performance. But they aren’t concerned about personal gain or recognition, and they tend to find the spotlight uncomfortable. Instead, they prefer to focus attention on the team and its performance.

It’s a question of emphasis, and humble leaders emphasize something greater than themselves. It’s a difference that makes all the difference.

Robert Hogan, Ph.D., is the founder and president of Hogan Assessments. The first psychologist to determine the link between personality and organizational effectiveness, today he is the leading authority on personality assessment and leadership.

Ryne Sherman, Ph.D., is the chief science officer of Hogan Assessments. Prior to joining Hogan, he was an associate professor in the department of psychology at Texas Tech University, where he researched the importance of individual differences and the psychological properties of situations, and he developed tools for data analysis.

Scott Gregory, Ph.D., is the chief executive officer of Hogan Assessments. Prior to joining Hogan, he was the vice president of talent management and organizational development at Pentair, and a consultant for Personnel Decisions International and MDA Leadership Consulting.

Source: Talent Quarterly